The cyber revolution has been going on for almost forty years now. Computing started with powerful computers but remained a matter for large professional structures. Everything changed in the 1980s with a revolution that went through several phases:

- 1980s: arrival of the personal computer (the PC, in its DOS-Windows and Mac versions);

- 1990s: eruption of the Internet: computers communicate with each other. A web is set up;

- 2000s: Arrival of Net 2.0 with the multiplication of blogs and other personal websites. From now on, the individual is no longer a consumer of information, s/he becomes a producer. Their traffic is analysed by massive data algorithms (Big Data). The GAFAs are taking off.

- 2010s: widespread use of smartphones. Connectivity becomes ultra mobile. New artificial intelligence techniques (using neural networks and machine learning) become widespread. Cloud computing becomes the norm.

- 2020s: The current wave is expected to build on the implementation of 5G and the massification of increasingly autonomous connected objects.

These successive waves have brought about a real anthropological revolution. Our societies now operate entirely on the basis of cyberspace and its multiple layers (physical, software and information). What affects the citizen has also turned the business world upside down.

In the past, IT modernisation came from the business world to the individual. Now, the company is obliged to carry out two activities simultaneously: on the one hand, an increase in its equipment and the digitalisation of its procedures.

Today, a medium-sized company uses dozens of professional software packages and hundreds of machines, servers and cloud services: all of this is for its internal operations.

At the same time, it has to modify its procedures in depth to take account of the radical decentralisation of behaviour: relations with employees who have to be increasingly mobile, a trend accentuated by teleworking; but also relations with customers, as more and more B-to-C commercial activities are now carried out online. This explosion in IT usage brings with it obvious cybersecurity constraints.

Most companies have taken security measures and Information Systems Security Managers (ISSMs) have become essential links in professional organisations, even if their role is not always properly recognised. However, most of the time, their action is focused on the two primary layers of cyberspace, the physical and the software layer. The informational layer is generally less covered.

Information, at the heart of the third layer, is becoming an essential production factor in contemporary business. It takes many forms. For example, the analysis of customer data via Big Data (know your customer) uses micro-data collected in large numbers and processed to provide value.

But specific, more elaborate information is also essential to the company: it may be the price structure of an offer at the time of a commercial negotiation, or research and development projects, or the company’s strategic plan. Finally, the range of information processed by the company is enormous.

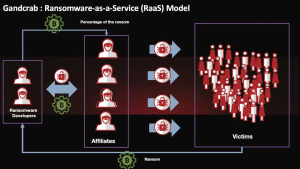

They are obviously not all on the same footing, but basically they are of interest to others: competitors as well as bandits. In the second case, it is a matter of stealing them in order to be paid: either by reselling them to a third party or by holding the company directly to ransom with a coding device (ransomware technique).

In this case, the attacker aims to take hostage as much data as possible, whether sensitive or not, but essential to the company’s operations. This risk weighs on all companies, whatever their size. In fact, in recent years, this technique has been industrialised (ransomware as a service) and all organisations can now be targeted.

Thinking that a small size organisation allows you to fly under the radar is a fatal strategy: just look at the number of small local authorities that have been taken hostage in the last three years. The phenomenon has become even more pronounced with the pandemic, which has forced most organisations to move to teleworking without having anticipated not only the technical aspects of this transition, but above all the security and data protection aspects linked to it.

But behind these criminal activities, it is clear that competitors can also spy on organisations: it is not a question of blocking a company’s activity, but of knowing its information capital (what is the status of a particular research project? what is its pricing position? what is its ambition with this customer?) in order to adjust its own strategy.

Several techniques exist: a lot of information can be detected by social engineering or so-called open source intelligence: for example, many company employees express themselves on social networks without realising what data they are communicating. But also, competitors can use spying methods, which is fraudulent.

The fact remains that many companies are not aware of these risks and do not see that the dilapidation of their information capital is a major obstacle. Before even thinking about taking measures, there is a need to convince management to become aware of this risk.

This risk is both highly probable and at the same time has maximum effects. Any risk mapping should deal with these risks as a priority. The protection of information capital must therefore become a priority for company management.

This is unfortunately not the case.